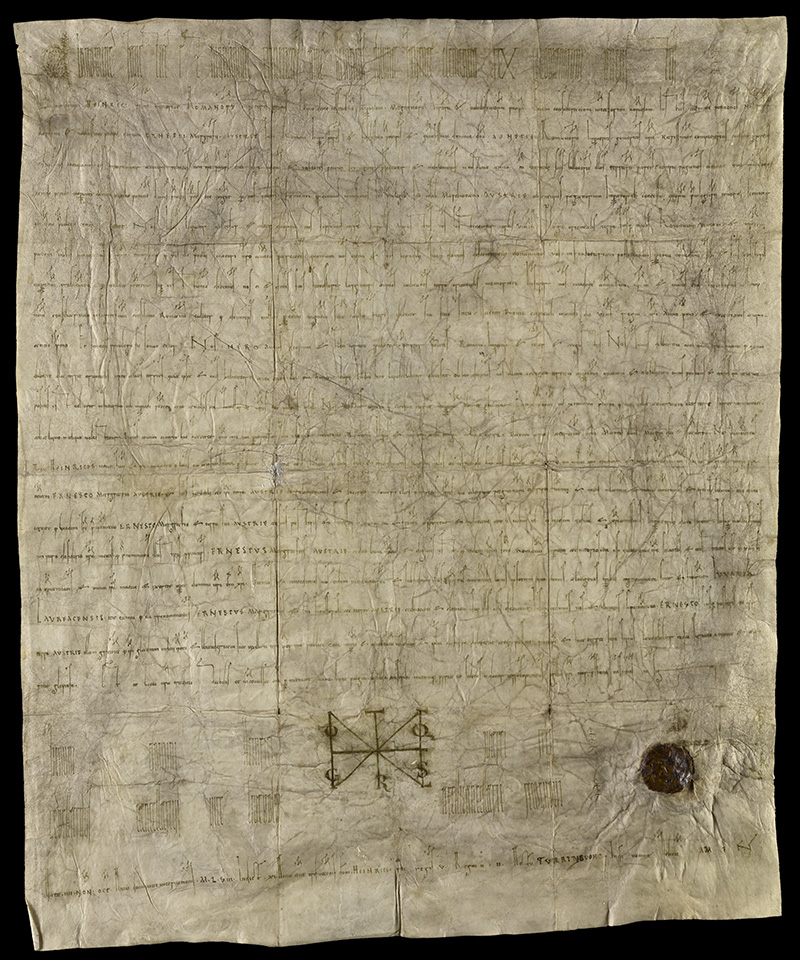

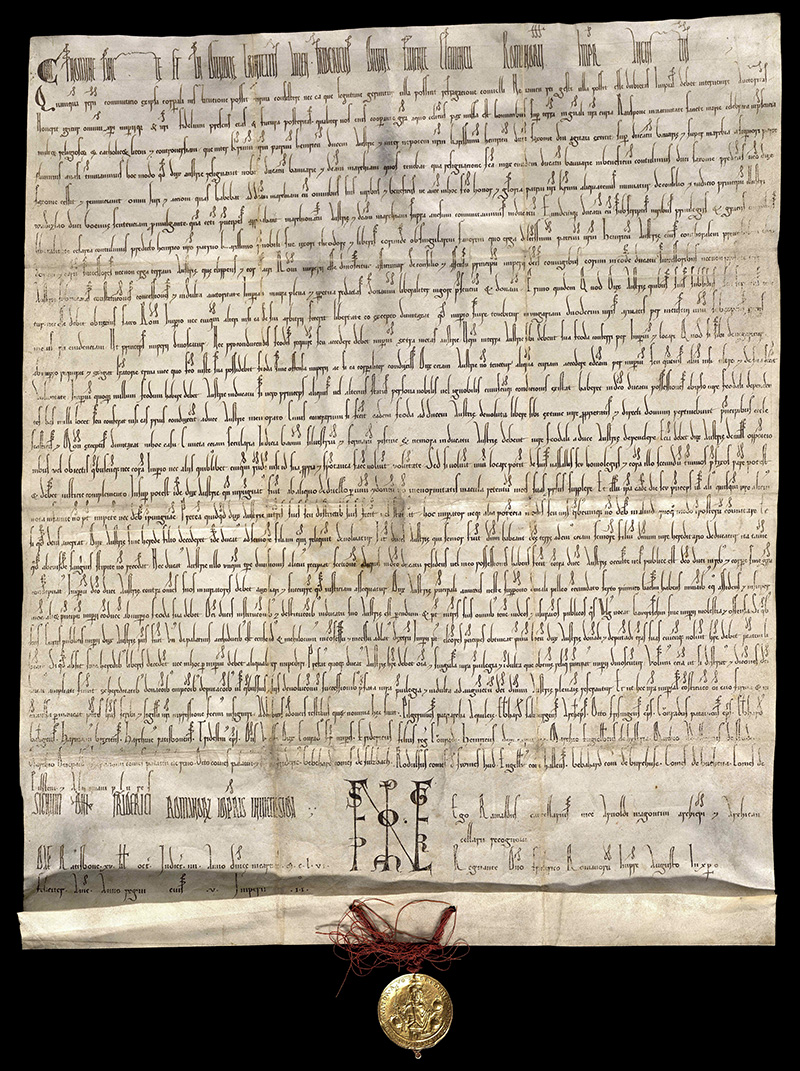

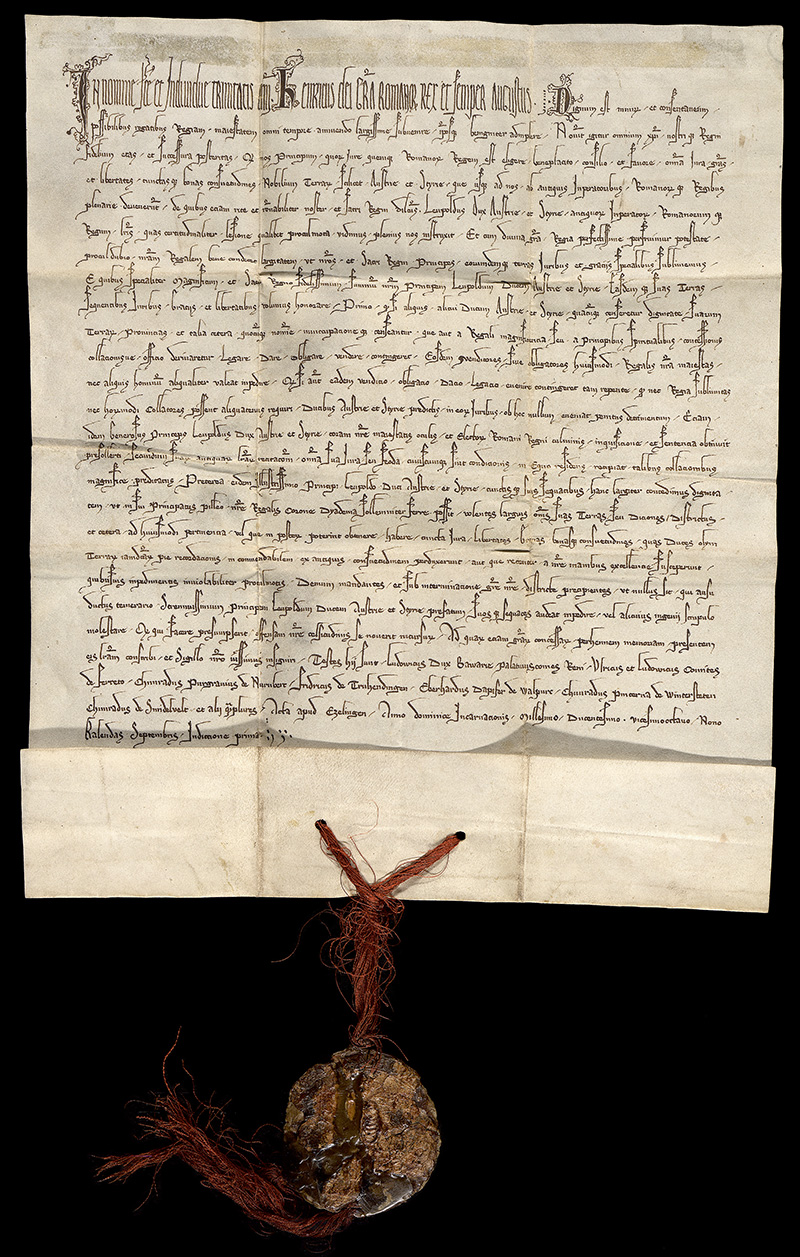

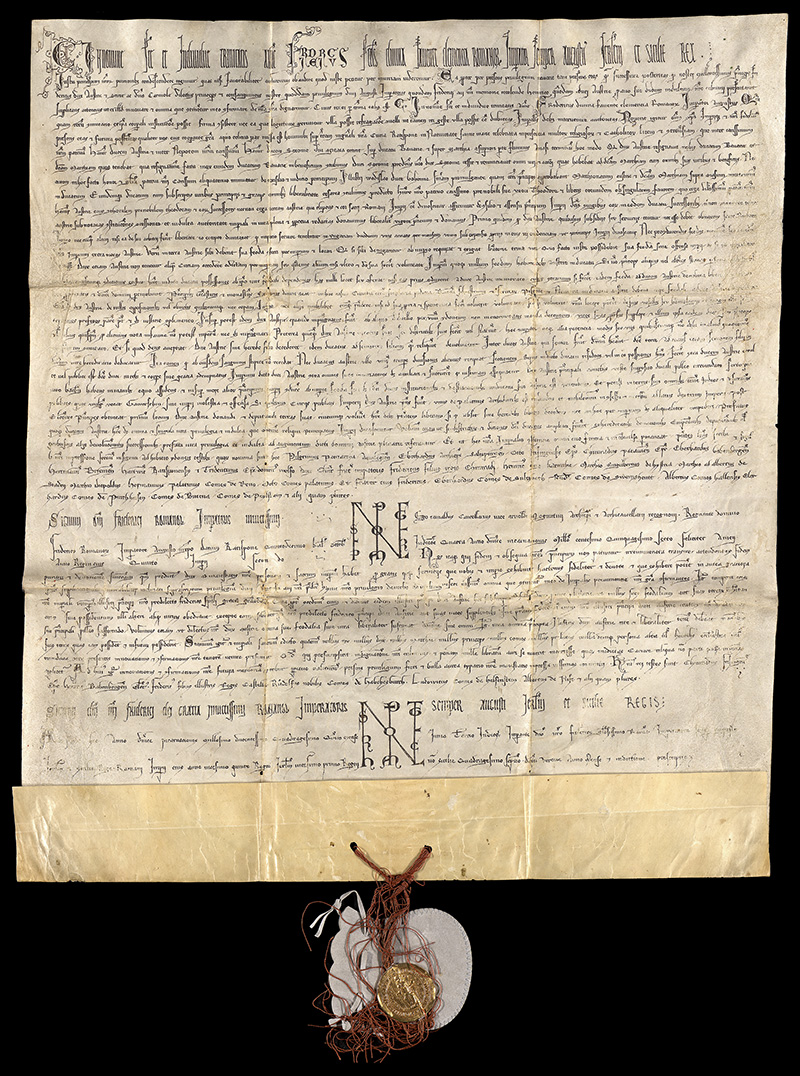

In the winter of 1358/59, Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, had five documents drawn up by his chancellery, which purported to be originals dating from the 1058, 1156, 1228, 1245, and 1283, and today are referred to as the Privilegium maius complex. In them, he asserted long-standing prerogative rights for the ducal rulers of Austria. In November 1360, he presented a copy, the so-called Vidimus, which shrewdly combined these fabricated documents with a number of genuine diplomas, to the deciding authority, Emperor Charles IV.

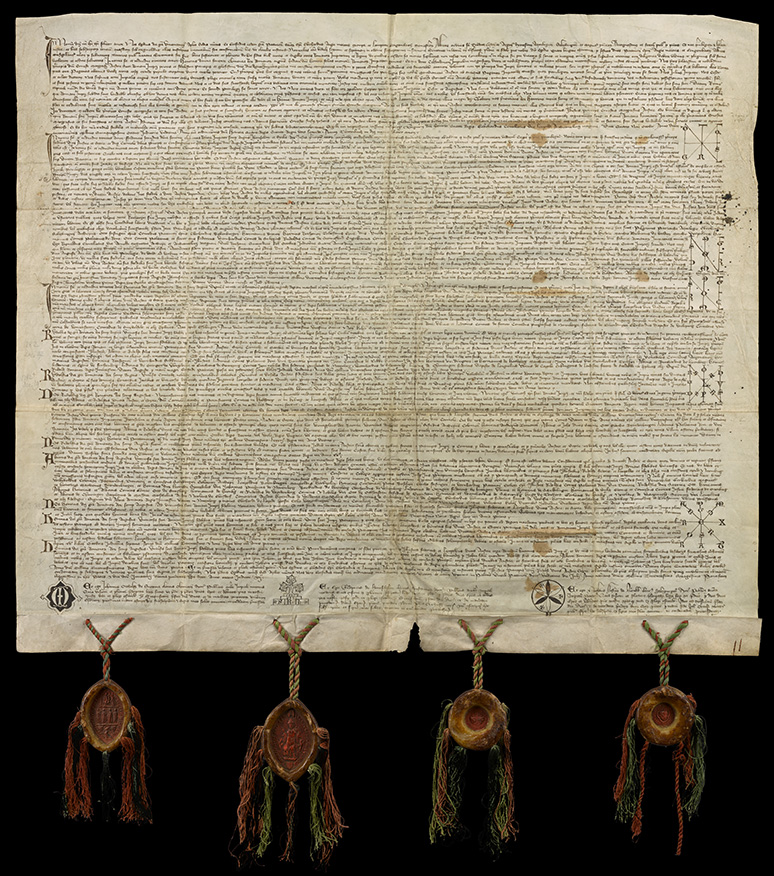

Among the many document forgeries of the medieval period, there is hardly another that went to such lengths to make documents look authentic. The information compiled here provides an in-depth insight into how material, content, and form were falsified to deceive contemporaries and explicates the methods used in recent time to examine the documents.

Kathrin Kininger, Archivist at the Austrian State Archives about the Privilegium Maius and its history

Illustration showing the College of Prince-Electors convened to elect Henry VII of Luxembourg as King of the Holy Roman Empire (1308) in the so-called Codex Balduini Trevirensis, c.1330/35. Koblenz, State Main Archive, dept. 1 C no. 1

© Landeshauptarchiv, Koblenz

The fourteenth century saw the rise of three dominant families in the Empire: the houses of Habsburg, Wittelsbach, and Luxembourg, each had several kings coming from them; they were related, they battled against and allied with each other in various constellations. It was also the time in which the constitutional foundation was laid for the development of the Holy Roman Empire until its end in 1806. In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charles IV first established an electoral body to choose the king, called the College of Prince-Electors. Seven Prince-Electors, three of them ecclesiastical and four secular nobles, from then on were the elite of the Empire. The Habsburgs, however, did not belong to that circle.

Duke Rudolf IV was the son-in-law of Emperor Charles IV (1316–1378), who felt compelled to respond to the fact that the Golden Bull of 1356 did not admit his dynasty, the Habsburgs, to the elite circle of Prince-Electors. In his eyes, this undercut his family’s prestige. So he resorted to fabrication as a means to assert the position of the Austrian lands in the Empire and the status of the Habsburgs among its princes. All in all, five deeds were drawn up, which in part were based on existing documents, and in part were completely fabricated. They purported to date back to the years 1058, 1156, 1228, 1245, and 1283. The broad time range was supposed to substantiate the legitimacy of the claims made. In November 1360, copies of the forgeries were, in the form of duplicates called a Vidimus, submitted to Emperor Charles IV for acknowledgement. However, this was not granted on all points, and the Duke had to retract some of the claims he had contended to be facts. About a hundred years after the fabrication of the bundle, though, the Habsburg Emperor Frederick III eventually acknowledged the assertions of the Austrian “letters of liberty.” With his catalogue of fictitious claims, Rudolf IV had thus created long-term legal facts which retained statutory validity until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. The debate about the genuineness and date of origin only started in the nineteenth century when the documents had long completely lost their political import following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire.

Representation of the Austrian “Bindenschild” (lit. “bind escutcheon,” after the name-giving white fess) with the Archducal hat and an inscription referring to the content of the documents fabricated in 1358/59, in the confirmation of the privileges of the House of Habsburg by the City of Vienna in 1512. Vienna, Austrian State Archives, House, Court, and State Archive, AUR 1512 XII 19

© Austrian State Archive

Portrait of Rudolf IV as Archduke of Austria, Vienna, c.1359/65. Vienna, Dom Museum Wien – Domkapitel, inv. no. L/11

© © Dom Museum Wien

Rudolf IV of Habsburg wanted to use the body of fabrications to establish a previously unknown rank and title – palatinus archidux – to be held by the dukes of Austria, as well as special insignia intended to display elements of an imperial crown – which later came to be called the Archducal hat. He had a seal cut for himself that was extravagant in several respects and promulgated this and other pretensions in word and image. Emperor Charles IV subsequently forbade Rudolf IV to use the arrogated titles, insignia and seal. However, in Vienna, his residence city, the young duke kept having himself portrayed with precisely those insignia: the scepter and the crown-like “Archducal hat.” There is no original hat extant from the time of Rudolf IV, but contemporary portraits of the duke on seals, in sculpture and painting convey an idea of its unusual shape, which perhaps took its inspiration from ancient coin portraits so as to make it look particularly old and tradition-honored.

For a technological examination, particularly for a comparison of manufacturing techniques and materials used in the making of the body of fabrications, the five forged documents of the Privilegium maius as well as the Vidimus were subjected to a series of examinations conducted at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in January 2017. In the process, preferably nondestructive examination methods were employed, which involved a number of radiation-diagnostic procedures, including different photographic techniques, infrared reflectography (IRR), and radiography.

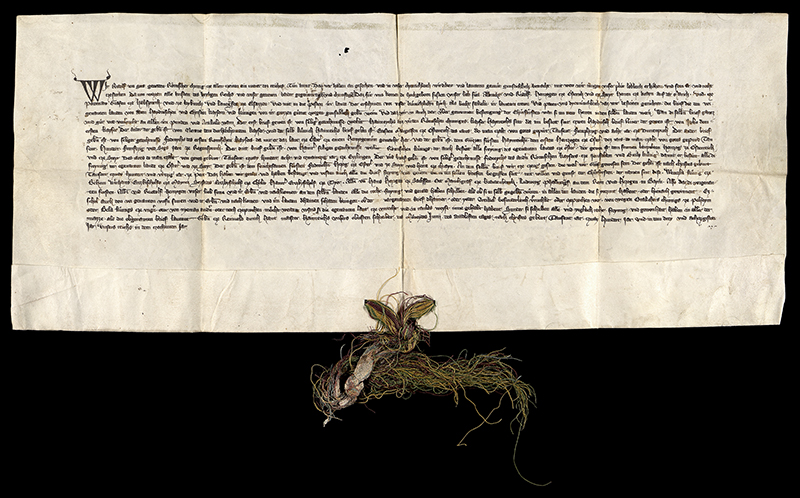

purportedly Thürnbuch,

October 4 1058

purportedly Regensburg,

September 17 1156

purportedly Esslingen,

August 24 1228

purportedly Verona,

June 1245

purportedly Rheinfelden,

June 11 1283

Vienna,

July 11 1360

Publication

Falsche Tatsachen

Das Privilegium maius und seine Geschichte