There were various forms of conducting legal transactions in the Middle Ages. South of the Alps what was known as the notary was widespread. Drawing up documents was the business of notaries, whose legitimacy was conferred by a higher authority. The notarial instrument, as this form of authentication is called, does not bear a seal, but instead the notary’s sign and signature. In order to assure legal security, the individual documents would invariably be entered in a book, the imbreviatur, kept by the notary.

This document was sealed by the issuers and additionally witnessed by three notaries authorised by the emperor, in line with the maxim “two are better than one”.

The Vidimus is written on an unusually large piece of calfskin parchment with almost the animal’s entire hide having been used. For such a large surface it was also necessary to make use of a sizeable portion of the stomach area, which produces parchment of inferior quality. The imaginary spine of the animal runs vertically down the document’s centre. Impressions of the tailbone are to be found on the upper margin. The hair side of the parchment was used as writing surface, a significant difference to the other documents.

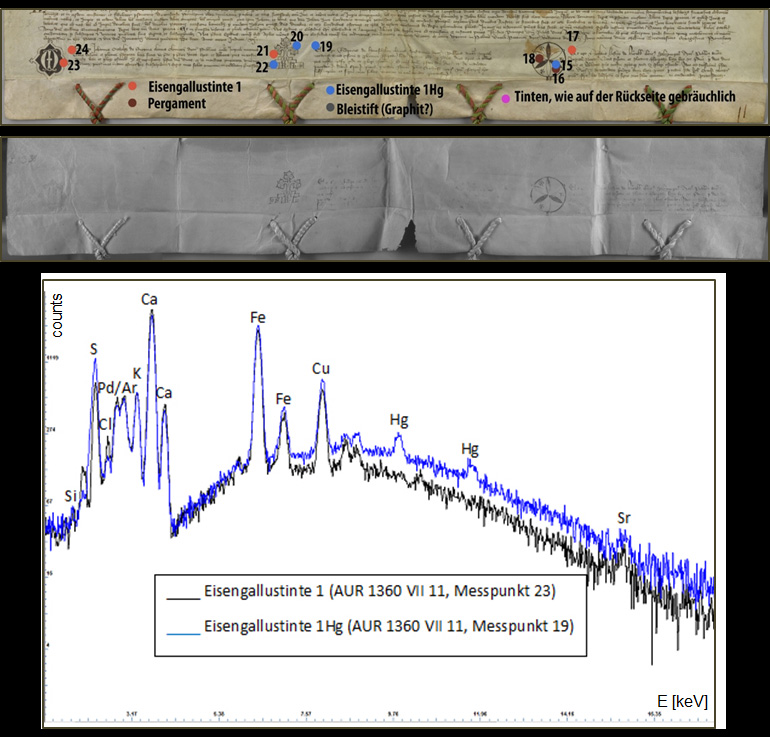

The central and right elements of the notarial signs on the lower edge of the Vidimus are drawn with iron gall inks of differing composition. These inks contain admixtures of material containing mercury and probably also carbon-based ink. As these are notarial signs of several persons, the divergence from the composition of ink used for the text is not only unremarkable, but indeed to be expected.

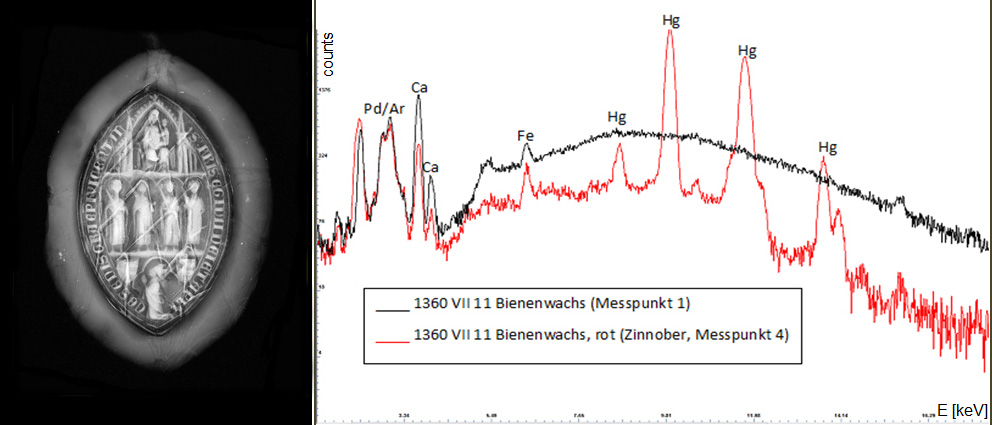

The round and ogival seals attached to red-green cords are performed as bowl seals. The bright bowls are made of beeswax to which chalk was presumably added. The wax plates within were pigmented red with cinnabar. This additive and the depth of the relief produce the high contrast of the wax plates in the x-ray radiographic images. These also reveal clearly the path of the cords within the seal, which supports the view that the seals and cords on the Vidimus are original.

Among the Privilegium maius documents this one is unique: differently than the other five this is genuine. This document, not the individual forged manuscripts, was presented to the emperor for confirmation. Duke Rudolf IV did not have the forgeries made for his own self-assurance alone, but also to have them confirmed by his father-in-law, Emperor Charles IV (1316–78), with the aim of enhancing their authenticity.

Rudolf IV requested a number of ecclesiastic notables to give their Vidimus to these documents, i.e. the bishops and abbots attested to the genuineness of the copies of the documents by affixing their seals. Cleverly Rudolf not only had the forgeries but also four authentic documents confirmed. In this way the forged diplomas are elegantly integrated into a factual chronology. As the texts of all eleven documents are reproduced in their entirety the Vidimus is of extraordinary dimensions, measuring almost one square metre.

The papal nuncio Aegidius, bishop of Vicenza, Gottfried, Bishop of Passau, Abbot Eberhard of Rheinau am Zellersee, and Abbot Lampert of Gengenbach confirm to Duke Rudolf IV of Austria deeds concerning privileges of the House of Austria (Vidimus).

Vienna, 11 July 1360

Parchment, four seals on red and green silk cords

Vienna, Austrian State Archives, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, AUR 1360 VII 11

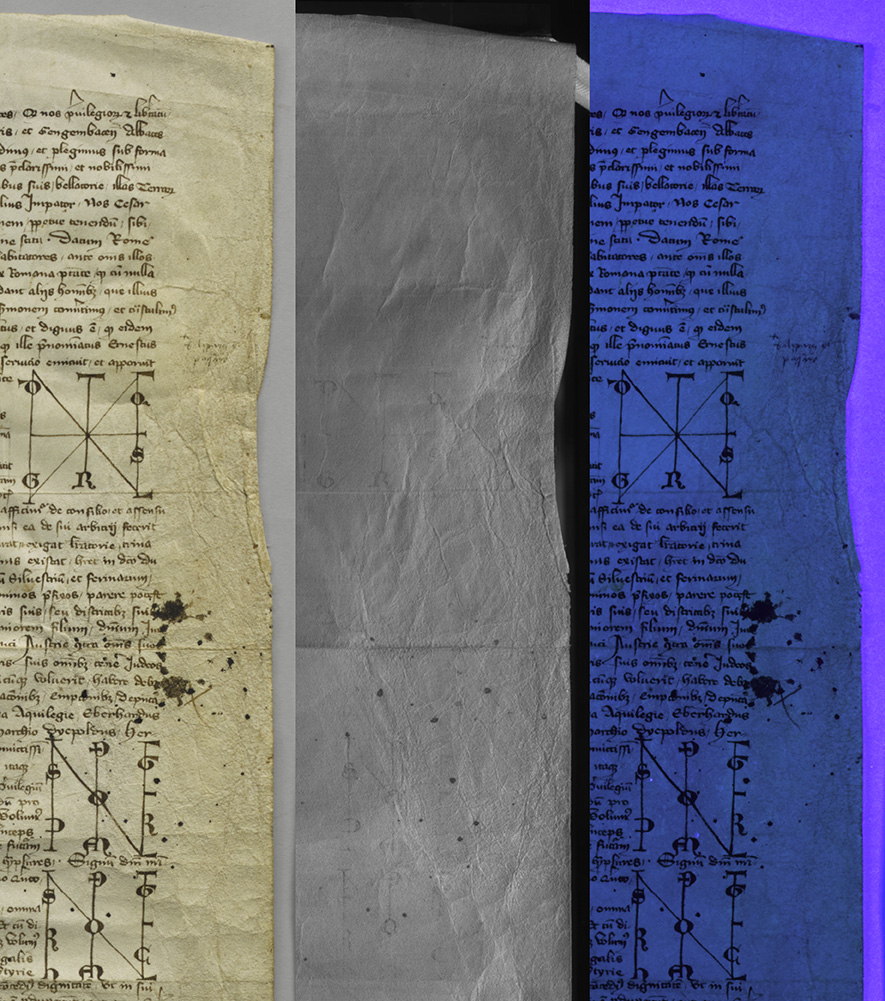

A photograph taken under raking light, that is lighting the object from the side at a very flat angle, can clearly reveal different topographic effects.

On the Vidimus too it is principally prominent creases and folds in the parchment that are visible. The script near the folds and creases has been markedly reduced as a result of mechanical exposure.

The use of ultraviolet (UV) light induces some materials, including many organic media, to manifest a differently coloured and characteristic fluorescence. UV radiation may also be completely obliterated by absorption. This may provide preliminary information about materials and divergent compositions of material. Indications of changes and the condition of object surfaces, for example, subsequent alterations and damage, often show up more clearly in photographic images taken under ultraviolet light.

Applying ultraviolet light rulings made for the text can be seen at several places, as well as brown discolorations of limited extent and stains left by dripped ink.

The technique of infrared reflectography (IRR) allows a more profound insight into the structure of objects. For the study of documents in particular IRR allows conclusions to be drawn about the inks used. The two most commonly employed types of ink, iron gall and carbon-based (soot) ink, differ clearly when exposed to infrared radiation.

On the right margin of the parchment knife marks left in the process of removing the skin are visible. The thinly applied ink, which under visible light appears brownish, disappears almost entirely applying IRR, indicating the use of iron gall ink. The rulings for the text, which are sporadically visible when exposed to ultraviolet light, are also to be seen by IRR.

When X-rays penetrate objects they are absorbed differently depending on the object’s thickness and the presence of heavy elements before being projected onto x-ray sensitive film.

The x-ray radiographic image of the extraordinarily large calfskin parchment shows clearly anatomical structures of the animal hide, as well as knife marks around the right margin remaining from the process of removing the skin. The text written in iron gall ink stands out plainly, as do rulings for the text. The rulings may have been drawn with a lead stylus, which would explain the high absorption of x-rays.